Stuart R. Gallant, MD, PhD

How do you bargain with a country with whom you are technically at war? That was the dilemma facing Israel and Lebanon last year. In October 2022, the two countries reached a deal addressing the maritime border separating the two Mediterranean nations, allowing the natural gas reserves adjoining the border to be developed. Today’s post involves many themes of negotiation: mediation, stakeholders not at the table, anchors, urgency, and international law.

National Rights in the Near Coastal Seas

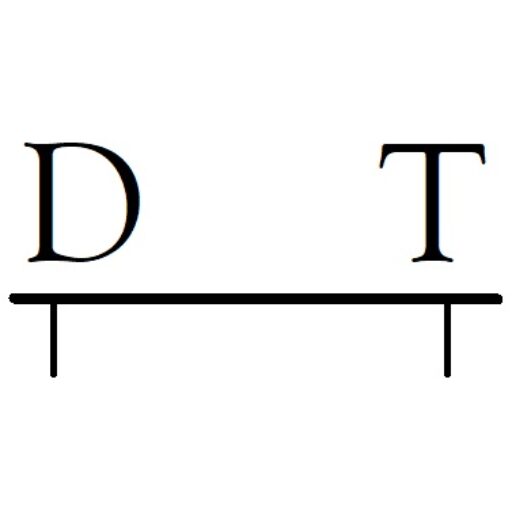

How do nations know what to expect with respect to maritime rights? This question lies at the heart of the negotiations between Israel and Lebanon. There are a broad set of principles laid out in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) which were negotiated in the decades following World War II. Some of the features defined within UNCLOS are included in this schematic diagram:

Coastal nations can claim rights in the waters adjacent to their territory based on the distance from the shoreline. A coastal nation may define laws and regulation and exploit resources within 12 nautical miles of the coast—the territorial sea. For reference, it is possible to see approximately 5 miles to sea from the coast—so the extent of the territorial sea is somewhat beyond the coastal horizon. In addition, customs, taxation, immigration, and pollution laws may be enforced a further 12 nautical miles—the contiguous zone. This prevents for example smugglers from hanging just beyond the territorial sea and sprinting in to drop off contraband. Out to 200 nautical miles from the coast, a nation has the sole right to exploit natural resources—the exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

These principles are clear, but issues can become muddier when national waters overlap, when two nations disagree on the interpretation of UNCLOS, or when negotiating countries are not parties to UNCLOS. In the eastern Mediterranean, Lebanon is party to UNCLOS, though Israel is not. Nevertheless, UNCLOS represents a standard against which bargaining positions can be measured.

The Israel-Lebanon Maritime Border

The Israel-Lebanon land border has been a flash point in the recent past, chiefly during the 1970s and 1980s with probing attacks from Lebanese territory and Israeli sponsorship of proxies within Lebanon. PLO attacks preceding Israeli invasions in 1978 and 1982, and Hezbollah attacks preceding Israeli invasion in 2006.

In the early 2000s, gas exploration took off in the eastern Mediterranean. Off the coast of Israel, natural gas discoveries started in 1999, but the two discoveries that changed Israel’s energy future were the 2009 discovery of the Tamar field (estimated at 310 billion cubic meters of gas) and the 2010 discover of the Leviathan field (estimated at 620 billion cubic meters of gas). Tamar, Leviathan, and other discoveries along Israel’s coast have allowed the small nation to target production of 40 billion cubic meters per year which places it in the top 25 exporters of natural gas in the world.

To exploit any natural gas discoveries adjacent to Israel’s north and Lebanon’s south, a maritime border had to be established. With a defined border, blocks could then be delineated within coastal waters, and international energy companies would be able to bid for exploration and commercialization rights. In 2010, US diplomat Frederic Hof began mediation between Israel and Lebanon to establish the maritime border. At that time, the Karish and Qana fields were unknown. In the absence of data about offshore natural resources, both parties advanced proposed borders:

Per UNCLOS, maritime borders of neighboring countries are drawn perpendicular to the coast. With some slightly different assumptions, Israel offered Line 1 and Lebanon offered Line 23—both lines ostensibly perpendicular to the coast at the Israel-Lebanon land border. (Note: the above map is representative of the general features of the parties’ positions, but the lines on the above map were not drawn with GPS accuracy.) In a classic split the difference solution, Hof proposed an intermediate line between Line 1 and Line 23.

The discovery of significant gas reserves along the maritime border of Israel and Lebanon dramatically raised the stakes for any negotiation. In 2013, the Karish field (estimated at 85 billion cubic meters of gas) was discovered. Subsequently, the Qana field (possibly up to 400 billion cubic meters) was also discovered.

In 2011, the Lebanese government commissioned a study from the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office (UKHO) which resulted in Line 29. In 2020, the Lebanese side proposed Line 29 in response to maritime border talks stalling. This may have been a negotiating tactic to cast doubt on Israel’s development of the Karish field. Line 29 never became part of the formal Lebanese bargaining position—it hung in the background when talks resumed later.

Parties

This dispute was a two-sided negotiation with some interesting parties not represented at the bargaining table:

- Lebanon: Lebanon is a nation that has been divided by civil war and visited by foreign militaries, including the Israeli Defense Force, Syrian Army, and Palestinian Liberation Organization. Additionally, Hezbollah represents a proxy force for Iran and Syria. The country has racked up huge financial obligations ($100B in debt) without proportional benefit to its people. Natural gas revenue would not eliminate Lebanese indebtedness, but it would be a move in the right direction.

- Israel: Israel has a vibrant economy which was hampered until the early 2000s by a lack of energy independence. With increased economic ties to the regional economy, Israel hopes that diplomatic progress will follow, leading to more normal relations. Thus, natural gas is not merely a tool for increasing GDP, to Israel, it represents a potential tool for the advancement of peace efforts.

- United States: Through its good offices, the United States has invested significantly in these negotiations as a part of its Middle East regional and European political strategies. The US hopes that natural gas revenue will help stabilize the tenuous domestic political situation in Lebanon. And, the prospect of additional inputs of liquid natural gas (LNG) into energy hungry Europe is an added bonus in the wake of the Russo-Ukrainian war and loss of Russian natural gas supplies.

- Hezbollah: On July 2, 2022, launched three drones toward the Karish gas field, asserting its role as a stakeholder not represented at the bargaining table. The drones were shot down by Israeli forces, but the message was clear—Hezbollah could make production of natural gas difficult if the border issue was not settled. However, lest it appear that Hezbollah was angling for improved relations with Israel, the primary motivation of its stand was likely that the deteriorating economic situation in Lebanon weakened the group’s political power in the small nation [1]

- Israeli Opposition: In retrospect, we know that Benjamin Netanyahu was victorious in the Nov. 1, 2022 Israeli elections following the maritime border deal. But, at the time of the negotiation, he was in opposition and just another stakeholder not at the bargaining table. He made his dislike of the deal very clear in the press. Presumably, he had two reasons for criticizing the deal. First, Hezbollah had supported the deal with its drones, so he viewed the agreement as a capitulation to Hezbollah military action. Second, the bargain was struck by Yair Lapid’s government, and he no doubt felt obligated to cast shade on his rival. Since the agreement was completed, he has been quoted as saying that he will “neutralize” the agreement—he however did not say that he would abandon or disavow it.

Issues

In a sense, the issues involved in this negotiation were deceptively simple. Examining the maritime map of the Israel-Lebanon border, the issue seems to be literally one of how to slice the natural gas cake, but that ignores other issues that represented challenges and opportunities in the negotiation. One of the most important strategies of negotiation is to perceive all the issues at hand in order to take advantage of hidden breaks. Some issues and opportunities confronting the Israeli and Lebanese negotiators included:

- Ossified Negotiating Positions: In any negotiation that proceeds for an extended period of time, the positions of the principals risk becoming hardened and inflexible. In the case of this negotiation, the first attempt at mediation in 2010 had been followed by a long period without any progress.

- Regional Rivalry: Israel’s northern border has been the site of recurrent violence since Israeli independence in 1948. It can be tremendously difficult to work constructively with an old rival.

- Urgency of the Moment: As in the case of Nixon’s opening to China [2], the Israel-Lebanon maritime border negotiation benefited from some unique circumstances that created one-time incentives toward breakthrough. These include: 1) With global warming becoming an issue, hydrocarbon producing nations are under pressure to extract resources from the ground or leave them forever in place. If Israel and Lebanon do not pump out the Karish and Qana fields in the next few decades, it is possible that the opportunity will pass, like money left on the table. 2) The Lebanese treasury is under massive pressure as Lebanon’s GDP craters. 3) Both the Israeli and Lebanese governments were in flux. Israeli elections followed in late 2022 and the Lebanese government was in a caretaker role. So, neither side had time to spare before they might lose power. 4) Israel was ready to bring the Karish field into production in 2022, but without an agreement, there was risk of military attack on gas infrastructure from the Lebanese side of the border—something the Israeli military could deal with but which it no doubt preferred not to. 5) In the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, the world was short of natural gas due to the Russian supply to Europe being interrupted. So, negotiation of new natural gas agreements would be easy and lucrative from the supplier point of view.

Negotiation

Early mediation efforts in 2010-2012 by US diplomat Frederic Hof were described above. Unfortunately, although the issues had been explored, no concrete progress had been made.

Negotiations restarted in October 2020 with mediation by Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs David Schenker. The Lebanese asserted Line 29 which fell outside of the previously discussed Lines 1 and 23. This was what might be called a late-stage anchor. Early anchors can improve the bargaining position of a party [3]. Late-stage anchors signal one of two things: a shift of the balance of power in the negotiation toward the party offering the anchor or a willingness of the party offering the anchor to blow up the negotiation. Talks quickly deadlocked with the Israeli Energy Minister Yuval Steinitz tweeting hyperbolically [4], “Lebanon has changed its stance on its maritime border with Israel seven times.”

Amos Hochstein was appointed as the new US mediator in October 2021. A US diplomat born in Israel, Hochstein was familiar with the region, as well as having familiarity with US departments affected by the negotiation (the White House, State, Treasury, and Energy). A new mediator can often get stalled negotiations moving, and in this case, that seems to have been critical. He was able to shuttle between the two sides and apply pressure for compromise.

The US pressured the Lebanese side to abandon Line 29; nevertheless, the Lebanese side seems to have benefited from the late-stage anchor. The final line swung from the split-the-baby Hof line of 2010-2012 negotiations to the Lebanese offered Line 23—a victory for the Lebanese side.

Interestingly, there is another interpretation of what happened in the negotiation. The Israeli side relinquished some territory that it had earlier claimed (Line 1), but it gained some prospect for peace on its northern border. The agreement places two valuable economic assets along that border (Karish for the Israelis and Qana for the Lebanese), creating a powerful disincentive to future military conflict on Israel’s norther border. So, this may have been a sea-for-peace trade.

Once the new maritime border had been agreed on, the question became: how much of the gas is on the Lebanese side of Line 23 and how much is on the Israeli side? This was a theoretical question because the field remained unexplored at the time. The answer the two sides agreed to was in effect 83% on the Lebanese side and 17% on the Israeli side. The final deal was signed at the end of October, just prior to Israeli elections, and included the features:

- The first 5 kilometers are defined by the buoy line set by Israel for maritime security, farther out, Line 23 governs.

- 17% of profits from the Qana field go to Israel.

- US to mediate royalty disputes.

Conclusions

There are so many interesting themes to the Israel-Lebanon maritime border negotiation. They were ticked off in the discussion above (mediation, stakeholders not at the table, anchors, urgency, international law). One that bears additional reflection is the negotiation model. There are several negotiation models that apply to various bargaining situations (competitive, problem solving, compromise, allocation). Clearly, some see this negotiation as competitive—for instance, Netanyahu has made it clear that he thinks Israel conceded to Hezbollah—he is embracing a competitive view of the negotiation. But there are other aspects. Israel compromised regarding the final line—a consideration that may (or may not) pay off in the long run in terms of improved relations with the US (who appreciated the support of its diplomacy) and with Lebanon. There was an allocative aspect to the negotiation—which country would receive what fraction of the gas reserve? Allocative negotiations often proceed in the face of imperfect knowledge of the size of the asset, but this type of negotiation is benefited as more information is provided. Given that the undersea gas fields of the eastern Mediterranean were better understood in 2022 than 2010, this increased knowledge aided a final settlement.

[1] Marsi, F. “What to know about the Israel-Lebanon maritime border deal,” Al Jazeera, Oct 14 (2022).

[2] Gallant, S.R. “Opening to China,” DiscussingTerms, Dec. 1 (2022). discussingterms.com/2022/12/01/opening-to-china/

[3] Gallant, S.R. “Making an Offer,” DiscussingTerms, Jan. 9 (2023). discussingterms.com/2023/01/09/negotiation-tip-making-an-offer/

[4] Daily Sabah. “Israel accuses Lebanon of changing stance on maritime border,” Nov. 20 (2020).

Disclaimer: DiscussingTermsTM provides commentary on topics related to negotiation. The content on this website does not constitute strategic, legal, or financial advice. Consult an appropriately skilled professional, such as a corporate board member, lawyer, or investment counselor, prior to undertaking any action related to the topics discussed on DiscussingTerms.com.